|

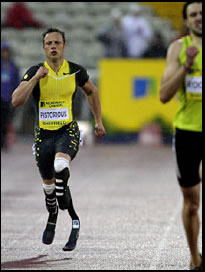

| Oscar Pistorius running in a marathon |

So life can be fair after all. After the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) ruled against Oscar Pistorius's participation in the Olympic trials because his prosthetic limbs - referred to as Cheetahs - supposedly gave him an advantage, a higher court overruled the IAAF, claiming that Pistorius has no advantage over non-disabled athletes and in fact may be at a disadvantage taking turns, getting out of the blocks, and running on a wet track. Even George Vecsey, the highly respected sports writer for the New York Times, agreed it was the right decision and softened his opinion that Pistorius had an unfair advantage: "While I still have my doubts about the implications of these springy lower limbs - both in magnifying speed and affecting other runners - I find myself applauding the narrow one-case judgment of the court."

The IAAF based its decision on studies that were conducted in a German lab by Dr. Bruggemann, who concluded that the Cheetahs were energy-efficient. Pro bono attorneys for Mr. Pistorius had their own independent tests performed by a team of researchers at MIT, who concluded that the South African runner did not gain any advantage over non-disabled runners. The unanimous ruling by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) sent shockwaves through the international world of track and field, notably diminishing the IAAF ruling and making it clear that discrimination had no place in sports.

We can thank many great leaders in the disability movement for society's moderating attitudes toward people with disabilities. While we still have a long way to go, especially in certain pockets of the world where people with disabilities are discriminated against in every aspect of society, we are much better off than we were a few decades ago. In the U.S., the disability movement began in full force in the early 1970s with the passage of two historic bills, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975. During the 1980s, the movement picked up steam and in 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed, which is considered by many to be the long-awaited civil rights bill for people with disabilities.

Disabled sports also had a major role in changing attitudes. Paralympic athletes demonstrated, on the world stage, excellence in sports competition and proved that their capability to reach the highest levels of human performance was no different than that of non-disabled athletes. Respect always seems to precede acceptance.

Pistorius is still a long way from qualifying for the Olympics. His personal best in the 400-meter run is 46.33 seconds and he must run 45.55 seconds to qualify. To a non-runner, that doesn't sound like a lot, but to those who live and breathe track and field, 0.8 seconds is an eternity that could take another 4 years of high-level training. Nonetheless, the fact that the highest court in track and field came down on the side of a disabled athlete speaks volumes. As one of Pistorius's lawyers was quoted after the decision, "It's not the device that makes Oscar fast, it's Oscar!" Let this be a wake-up call to the international community that people with disabilities will no longer be discriminated against in any sport at any level of competition. Human diversity is here to stay and there is a place at the table for everyone.