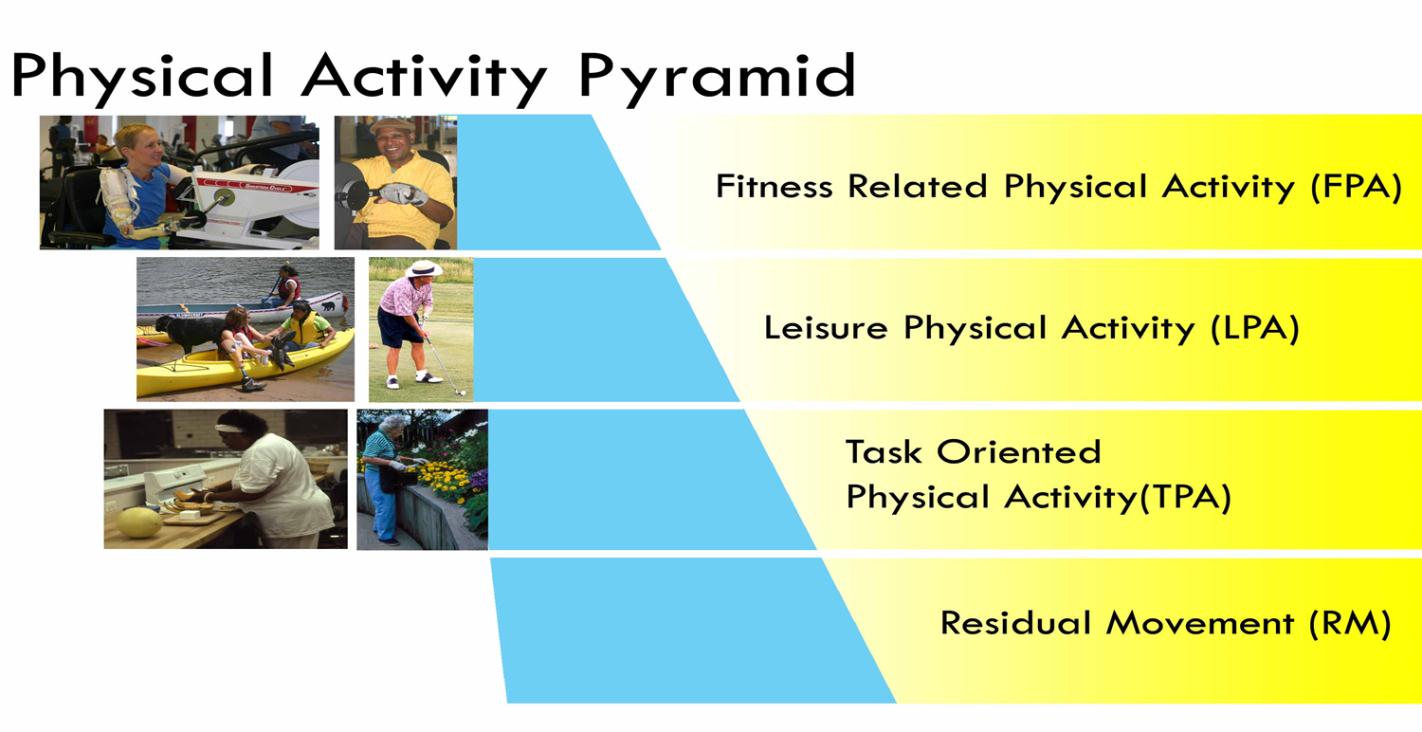

In the big picture of physical activity, everything counts! Running a 5k, sweating during spin or Krank class, and lifting weights are not the only examples of physical activity. Cleaning the house, planting flowers, walking while grocery shopping, and taking the dog out all count, too! The catch is changing our perspective. There are four categories of physical activity: fitness related physical activity, leisure physical activity, task-oriented physical activity, and residual movement. Each category has a place and counts towards physical activity as a whole.

Fitness-Related Physical Activity

This category of physical activity is at the top of the pyramid and consists of what is commonly known as exercise. Examples include aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities. Aerobic activity refers to cycling, pushing in a wheelchair, running, brisk walking, dancing, playing basketball, swimming and using cardiovascular equipment at a gym, for example. Muscle-strengthening activity refers to lifting weights, using resistance bands, and body weight movements such as push-ups and planks. Benefits of this type of physical activity include lowered risk of heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes, and some cancers. Additional benefits include prevention of weight gain, weight loss, improved cardiovascular and muscular fitness, prevention of falls, and reduced depression. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (PAG) provide science-based guidance to help Americans age six and older improve their health through appropriate physical activity¹. The key guidelines for adults are:

Key Guidelines for Adults¹

- For substantial health benefits, adults should do at least 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) a week of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity. Aerobic activity should be performed in episodes of at least 10 minutes and preferably should be spread throughout the week.

- Adults with disabilities who are able to should get at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity, or 75 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity.

- For additional and more extensive health benefits, adults should increase their aerobic physical activity to 300 minutes (5 hours) a week of moderate-intensity, or 150 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity. Additional health benefits are gained by engaging in physical activity beyond this amount.

- Adults should also do muscle-strengthening activities that are moderate- or high-intensity and involve all major muscle groups on two or more days per week, as these activities provide additional health benefits.

- Adults with disabilities who are able to should also do muscle-strengthening activities of moderate- or high-intensity that involve all major muscle groups on two or more days a week, as these activities provide additional health benefits.

- When adults with disabilities are not able to meet the Guidelines, they should engage in regular physical activity according to their abilities and should avoid inactivity.

- All adults should avoid inactivity. Some physical activity is better than none, and adults who participate in any amount of physical activity gain some health benefits.

The last two guidelines are crucial to changing our perspectives on physical activity. The best advice is to start small and work your way up to meeting or exceeding the PAG. Some activity is better than none; if you have 10 minutes, use them to be physically active and let those bursts of activity add up throughout the day. Avoid inactivity and engage in activity according to your abilities. Chances are that this is not so hard when we change the way we think about physical activity by incorporating some of the other categories discussed below.

The NCHPAD website has a wealth of information to help you find ways to incorporate fitness-related physical activity. Start in the Exercise and Fitness category, with programs such as 14 Weeks to a Healthier You! or Champion’s Rx, and read Get the Facts on physical activity.

Leisure Physical Activity

If going to a gym or exercising in a structured way does not sound appealing to you, start with this category and build your love for movement. The word leisure is defined as, “time free from the demands of work or duty”². Combining this definition with physical activity could produce a much more enjoyable experience. Examples of leisure-time physical activity include walking, gardening, hiking, active transportation, cleaning, play, and sports participation. A study conducted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) found that leisure-time physical activity can extend life expectancy by as much as 4.5 years, so do not overlook this category when thinking about physical activity.

If going to a gym or exercising in a structured way does not sound appealing to you, start with this category and build your love for movement. The word leisure is defined as, “time free from the demands of work or duty”². Combining this definition with physical activity could produce a much more enjoyable experience. Examples of leisure-time physical activity include walking, gardening, hiking, active transportation, cleaning, play, and sports participation. A study conducted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) found that leisure-time physical activity can extend life expectancy by as much as 4.5 years, so do not overlook this category when thinking about physical activity.

Task-Oriented Physical Activity

This category can be used to set obtainable goals that will provide you with a sense of accomplishment and success. Examples of task-oriented physical activity include doing household chores such as laundry, getting the mail, taking out the dog, and cleaning up a room. You will see that some activities in this category can cross over into the leisure-time physical activity category. The focus is that the type of activity you are doing is task-related and includes an end goal.

Residual Movement

The last category of physical activity is residual movement. This includes movement that is not categorized as any of the other types of physical activity. These movements are performed in conjunction with the energy that our body utilizes to exist and can be connected to what we do to reduce sedentary time. The goal is to move as much as you can during the day and avoid being sedentary.

A Lifestyle of Movement

Hopefully after reading this article you have gained a renewed perspective as to what actually counts towards physical activity . Like I said, you might be surprised by how much you are actually getting in! As we change our perspectives on physical activity moving into this holiday season and New Year, try incorporating more movement into your lifestyle. You may have values relating to your family, faith, and happiness; add movement as another personal value and see how it can truly transform several aspects of your life.

Sources:

- ¹2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/summary.aspx

- ²"leisure." Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. 05 Dec. 2014. <Dictionary.com http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/leisure>.

The information provided here is offered as a service only. The National Center on Health, Physical Activity, and Disability and the UAB/Lakeshore Research Collaborative does not formally recommend or endorse the equipment listed. As with any products or services, consumers should investigate and determine on their own which equipment best fits their needs and budget.